The domestic dog (Canis lupus familiaris) is a subspecies of the gray wolf (Canis lupus), a member of the Canidae family of the mammalian order Carnivora. The term "domestic dog" is generally used for both domesticated and feral varieties. The dog was the first domesticated animal and has been the most widely kept working, hunting, and pet animal in human history. The word "dog" may also mean the male of a canine species,as opposed to the word "bitch" for the female of the species.

MtDNA evidence shows an evolutionary split between the modern dog's lineage and the modern wolf's lineage around 100,000 years ago but, as of 2013, the oldest fossil specimens genetically linked to the modern dog's lineage date to approximately 33,000–36,000 years ago.Dogs' value to early human hunter-gatherers led to them quickly becoming ubiquitous across world cultures. Dogs perform many roles for people, such as hunting, herding, pulling loads, protection, assisting police and military, companionship, and, more recently, aiding handicapped individuals. This impact on human society has given them the nickname "man's best friend" in the Western world. In some cultures, however, dogs are also a source of meat.In 2001, there were estimated to be 400 million dogs in the world.

Most breeds of dogs are at most a few hundred years old, having been artificially selected for particular morphologies and behaviors by people for specific functional roles. Through this selective breeding, the dog has developed into hundreds of varied breeds, and shows more behavioral and morphological variation than any other land mammal. For example, height measured to the withers ranges from 15.2 centimetres (6.0 in) in the Chihuahua to about 76 cm (30 in) in the Irish Wolfhound; color varies from white through grays (usually called "blue") to black, and browns from light (tan) to dark ("red" or "chocolate") in a wide variation of patterns; coats can be short or long, coarse-haired to wool-like, straight, curly, or smooth.It is common for most breeds to shed this coat.

"Dog" is the common use term that refers to members of the subspecies Canis lupus familiaris (canis, "dog"; lupus, "wolf"; familiaris, "of a household" or "domestic"). The term can also be used to refer to a wider range of related species, such as the members of the genus Canis, or "true dogs", including the wolf, coyote, and jackals, or it can refer to the members of the tribe Canini, which would also include the African wild dog, or it can be used to refer to any member of the family Canidae, which would also include the foxes, bush dog, raccoon dog, and others.Some members of the family have "dog" in their common names, such as the raccoon dog and the African wild dog. A few animals have "dog" in their common names but are not canids, such as the prairie dog.

The English word "dog" comes from Middle English dogge, from Old English docga, a "powerful dog breed".The term may possibly derive from Proto-Germanic *dukkōn, represented in Old English finger-docce ("finger-muscle").The word also shows the familiar petname diminutive -ga also seen in frogga "frog", picga "pig", stagga "stag", wicga "beetle, worm", among others. Due to the archaic structure of the word, the term dog may ultimately derive from the earliest layer of Proto-Indo-European vocabulary, reflecting the role of the dog as the earliest domesticated animal.

In 14th-century England, "hound" (from Old English: hund) was the general word for all domestic canines, and "dog" referred to a subtype of hound, a group including the mastiff. It is believed this "dog" type of "hound" was so common, it eventually became the prototype of the category "hound". By the 16th century, dog had become the general word, and hound had begun to refer only to types used for hunting.Hound, cognate to German Hund, Dutch hond, common Scandinavian hund, and Icelandic hundur, is ultimately derived from the Proto-Indo-European *kwon- "dog", found in Sanskrit kukuur (कुक्कुर),Welsh ci (plural cwn), Latin canis, Greek kýōn, and Lithuanian šuõ.

In breeding circles, a male canine is referred to as a dog, while a female is called a bitch (Middle English bicche, from Old English bicce, ultimately from Old Norse bikkja). A group of offspring is a litter. The father of a litter is called the sire, and the mother is called the dam. Offspring are, in general, called pups or puppies, from French poupée, until they are about a year old. The process of birth is whelping, from the Old English word hwelp (cf. German Welpe, Dutch welp, Swedish valpa, Icelandic hvelpur). The term "whelp" can also be used to refer to the young of any canid, or as a (somewhat archaic) alternative to "puppy".

Taxonomy.

In 1753, the father of modern biological taxonomy, Carl Linnaeus, listed among the types of quadrupeds familiar to him, the Latin word for dog, canis. Among the species within this genus, Linnaeus listed the fox, as Canis vulpes, wolves (Canis lupus), and the domestic dog, (Canis canis).

In later editions, Linnaeus dropped Canis canis and greatly expanded his list of the Canis genus of quadrupeds, and by 1758 included alongside the foxes, wolves, and jackals and many more terms that are now listed as synonyms for domestic dog, including aegyptius (hairless dog), aquaticus, (water dog), and mustelinus (literally "badger dog"). Among these were two that later experts have been widely used for domestic dogs as a species: Canis domesticus and, most predominantly, Canis familiaris, the "common" or "familiar" dog.

The domestic dog was accepted as a species in its own right until overwhelming evidence from behavior, vocalizations, morphology, and molecular biology led to the contemporary scientific understanding that a single species, the gray wolf, is the common ancestor for all breeds of domestic dogs.In recognition of this fact, the domestic dog was reclassified in 1993 as Canis lupus familiaris, a subspecies of the gray wolf Canis lupus, by the Smithsonian Institution and the American Society of Mammalogists. C. l. familiaris is listed as the name for the taxon that is broadly used in the scientific community and recommended by ITIS, although Canis familiaris is a recognised synonym.

Since that time, C. domesticus and all taxa referring to domestic dogs or subspecies of dog listed by Linnaeus, Johann Friedrich Gmelin in 1792, and Christian Smith in 1839, lost their subspecies status and have been listed as taxonomic synonyms for Canis lupus familiaris.

History and evolution

Although experts largely disagree over the details of dog domestication, it is agreed that human interaction played a significant role in shaping the subspecies.Domestication may have occurred initially in separate areas, particularly Siberia and Europe. Currently it is thought domestication of our current lineage of dog occurred sometime as early as 15,000 years ago and arguably as late as 8500 years ago. Shortly after the latest domestication, dogs became ubiquitous in human populations, and spread throughout the world.

Emigrants from Siberia likely crossed the Bering Strait with dogs in their company, and some experts suggest the use of sled dogs may have been critical to the success of the waves that entered North America roughly 12,000 years ago,although the earliest archaeological evidence of dog-like canids in North America dates from about 9,400 years ago.Dogs were an important part of life for the Athabascan population in North America, and were their only domesticated animal. Dogs also carried much of the load in the migration of the Apache and Navajo tribes 1,400 years ago. Use of dogs as pack animals in these cultures often persisted after the introduction of the horse to North America.

The current consensus among biologists and archaeologists is that the dating of first domestication is indeterminate,although more recent evidence shows isolated domestication events as early as 33,000 years ago.There is conclusive evidence the present lineage of dogs genetically diverged from their wolf ancestors at least 15,000 years ago,but some believe domestication to have occurred earlier. Evidence is accruing that there were previous domestication events, but that those lineages died out.

It is not known whether humans domesticated the wolf as such to initiate dog's divergence from its ancestors, or whether dog's evolutionary path had already taken a different course prior to domestication. For example, it is hypothesized that some wolves gathered around the campsites of paleolithic camps to scavenge refuse, and associated evolutionary pressure developed that favored those who were less frightened by, and keener in approaching, humans.

The bulk of the scientific evidence for the evolution of the domestic dog stems from morphological studies of archaeological findings and mitochondrial DNA studies. The divergence date of roughly 15,000 years ago is based in part on archaeological evidence that demonstrates the domestication of dogs occurred more than 15,000 years ago,and some genetic evidence indicates the domestication of dogs from their wolf ancestors began in the late Upper Paleolithic close to the Pleistocene/Holocene boundary, between 17,000 and 14,000 years ago.But there is a wide range of other, contradictory findings that make this issue controversial.There are findings beginning currently at 33,000 years ago distinctly placing them as domesticated dogs evidenced not only by shortening of the muzzle but widening as well as crowding of teeth.

Archaeological evidence suggests that the latest point at which dogs could have diverged from wolves was roughly 15,000 years ago, although it is possible they diverged much earlier.In 2008, a team of international scientists released findings from an excavation at Goyet Cave in Belgium declaring a large, toothy canine existed 31,700 years ago and ate a diet of horse, musk ox and reindeer.

Prior to this Belgian discovery, the earliest dog bones found were two large skulls from Russia and a mandible from Germany dated from roughly 14,000 years ago.Remains of smaller dogs from Natufian cave deposits in the Middle East, including the earliest burial of a human being with a domestic dog, have been dated to around 10,000 to 12,000 years ago.There is a great deal of archaeological evidence for dogs throughout Europe and Asia around this period and through the next two thousand years (roughly 8,000 to 10,000 years ago), with specimens uncovered in Germany, the French Alps, and Iraq, and cave paintings in Turkey.The oldest remains of a domesticated dog in the Americas were found in Texas and have been dated to about 9,400 years ago.

DNA studies

DNA studies have provided a wide range of possible divergence dates, from 15,000 to 40,000 years ago, to as much as 100,000 to 140,000 years ago.These results depend on a number of assumptions.Genetic studies are based on comparisons of genetic diversity between species, and depend on a calibration date. Some estimates of divergence dates from DNA evidence use an estimated wolf-coyote divergence date of roughly 700,000 years ago as a calibration.If this estimate is incorrect, and the actual wolf-coyote divergence is closer to one or two million years ago, or more,then the DNA evidence that supports specific dog-wolf divergence dates would be interpreted very differently.

Furthermore, it is believed the genetic diversity of wolves has been in decline for the last 200 years, and that the genetic diversity of dogs has been reduced by selective breeding. This could significantly bias DNA analyses to support an earlier divergence date. The genetic evidence for the domestication event occurring in East Asia is also subject to violations of assumptions. These conclusions are based on the location of maximal genetic divergence, and assume hybridization does not occur, and that breeds remain geographically localized. Although these assumptions hold for many species, there is good reason to believe that they do not hold for canines.

Genetic analyses indicate all dogs are likely descended from a handful of domestication events with a small number of founding females,although there is evidence domesticated dogs interbred with local populations of wild wolves on several occasions.Data suggest dogs first diverged from wolves in East Asia, and these domesticated dogs then quickly migrated throughout the world, reaching the North American continent around 8000 BC. The oldest groups of dogs, which show the greatest genetic variability and are the most similar to their wolf ancestors, are primarily Asian and African breeds, including the Basenji, Lhasa Apso, and Siberian Husky.Some breeds thought to be very old, such as the Pharaoh Hound, Ibizan Hound, and Norwegian Elkhound, are now known to have been created more recently.

A great deal of controversy surrounds the evolutionary framework for the domestication of dogs. Although it is widely claimed that "man domesticated the wolf," man may not have taken such a proactive role in the process.The nature of the interaction between man and wolf that led to domestication is unknown and controversial. At least three early species of the Homo genus began spreading out of Africa roughly 400,000 years ago, and thus lived for a considerable time in contact with canine species.

Despite this, there is no evidence of any adaptation of canine species to the presence of the close relatives of modern man. If dogs were domesticated, as believed, roughly 15,000 years ago, the event (or events) would have coincided with a large expansion in human territory and the development of agriculture. This has led some biologists to suggest one of the forces that led to the domestication of dogs was a shift in human lifestyle in the form of established human settlements. Permanent settlements would have coincided with a greater amount of disposable food and would have created a barrier between wild and anthropogenic canine populations.

Roles with humans

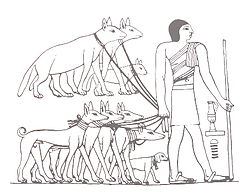

Early roles.

Wolves, and their dog descendants, would have derived significant benefits from living in human camps—more safety, more reliable food, lesser caloric needs, and more chance to breed.They would have benefited from humans' upright gait that gives them larger range over which to see potential predators and prey, as well as color vision that, at least by day, gives humans better visual discrimination.Camp dogs would also have benefitted from human tool use, as in bringing down larger prey and controlling fire for a range of purposes.

Humans would also have derived enormous benefit from the dogs associated with their camps.For instance, dogs would have improved sanitation by cleaning up food scraps.Dogs may have provided warmth, as referred to in the Australian Aboriginal expression "three dog night" (an exceptionally cold night), and they would have alerted the camp to the presence of predators or strangers, using their acute hearing to provide an early warning.

Anthropologists believe the most significant benefit would have been the use of dogs' sensitive sense of smell to assist with the hunt.The relationship between the presence of a dog and success in the hunt is often mentioned as a primary reason for the domestication of the wolf, and a 2004 study of hunter groups with and without a dog gives quantitative support to the hypothesis that the benefits of cooperative hunting was an important factor in wolf domestication.

The cohabitation of dogs and humans would have greatly improved the chances of survival for early human groups, and the domestication of dogs may have been one of the key forces that led to human success.

As pets.

"The most widespread form of interspecies bonding occurs between humans and dogs" and the keeping of dogs as companions, particularly by elites, has a long history. However, pet dog populations grew significantly after World War II as suburbanization increased. In the 1950s and 1960s, dogs were kept outside more often than they tend to be today (using the expression "in the doghouse" to describe exclusion from the group signifies the distance between the doghouse and the home) and were still primarily functional, acting as a guard, children's playmate, or walking companion. From the 1980s, there have been changes in the role of the pet dog, such as the increased role of dogs in the emotional support of their owners. People and dogs have become increasingly integrated and implicated in each other's lives,to the point where pet dogs actively shape the way a family and home are experienced.

There have been two major trends in the changing status of pet dogs. The first has been the 'commodification' of the dog, shaping it to conform to human expectations of personality and behaviour.The second has been the broadening of the concept of the family and the home to include dogs-as-dogs within everyday routines and practices.

There are a vast range of commodity forms available to transform a pet dog into an ideal companion. The list of goods, services and places available is enormous: from dog perfumes, couture, furniture and housing, to dog groomers, therapists, trainers and care-takers, dog cafes, spas, parks and beaches, and dog hotels, airlines and cemeteries. While dog training as an organized activity can be traced back to the 18th century, in the last decades of the 20th century it became a high profile issue as many normal dog behaviors such as barking, jumping up, digging, rolling in dung, fighting, and urine marking became increasingly incompatible with the new role of a pet dog. Dog training books, classes and television programs proliferated as the process of commodifying the pet dog continued.

The majority of contemporary dog owners describe their dog as part of the family,although some ambivalence about the relationship is evident in the popular reconceptualization of the dog-human family as a pack. A dominance model of dog-human relationships has been promoted by some dog trainers, such as on the television program Dog Whisperer. However it has been disputed that "trying to achieve status" is characteristic of dog–human interactions.Pet dogs play an active role in family life; for example, a study of conversations in dog-human families showed how family members use the dog as a resource, talking to the dog, or talking through the dog, to mediate their interactions with each other.

Another study of dogs' roles in families showed many dogs have set tasks or routines undertaken as family members, the most common of which was helping with the washing-up by licking the plates in the dishwasher, and bringing in the newspaper from the lawn. Increasingly, human family members are engaging in activities centered on the perceived needs and interests of the dog, or in which the dog is an integral partner, such as Dog Dancing and Doga.

According to the statistics published by the American Pet Products Manufacturers Association in the National Pet Owner Survey in 2009–2010, it is estimated there are 77.5 million dog owners in the United States. The same survey shows nearly 40% of American households own at least one dog, of which 67% own just one dog, 25% two dogs and nearly 9% more than two dogs. There does not seem to be any gender preference among dogs as pets, as the statistical data reveal an equal number of female and male dog pets. Yet, although several programs are undergoing to promote pet adoption, less than a fifth of the owned dogs come from a shelter.

Work.

Dogs have lived and worked with humans in so many roles that they have earned the unique nickname, "man's best friend", a phrase used in other languages as well. They have been bred for herding livestock, hunting (e.g. pointers and hounds), rodent control, guarding, helping fishermen with nets, detection dogs, and pulling loads, in addition to their roles as companions.

Service dogs such as guide dogs, utility dogs, assistance dogs, hearing dogs, and psychological therapy dogs provide assistance to individuals with physical or mental disabilities.Some dogs owned by epileptics have been shown to alert their handler when the handler shows signs of an impending seizure, sometimes well in advance of onset, allowing the owner to seek safety, medication, or medical care.

Dogs included in human activities in terms of helping out humans are usually called working dogs. Dogs of several breeds are considered working dogs. Some working dog breeds include Akita, Alaskan Malamute, Anatolian Shepherd Dog, Bernese Mountain Dog, Black Russian Terrier, Boxer, Bullmastiff, Doberman Pinscher, Dogue de Bordeaux, German Pinscher, German Shepherd, Giant Schnauzer, Great Dane, Great Pyrenees, Great Swiss Mountain Dog, Komondor, Kuvasz, Mastiff, Neapolitan Mastiff, Newfoundland, Portuguese Water Dog, Rottweiler, Saint Bernard, Samoyed, Siberian Husky, Standard Schnauzer, and Tibetan Mastiff.

Sports and shows.

Owners of dogs often enter them in competitions such as breed conformation shows or sports, including racing, sledding and agility competitions.

In conformation shows, also referred to as breed shows, a judge familiar with the specific dog breed evaluates individual purebred dogs for conformity with their established breed type as described in the breed standard. As the breed standard only deals with the externally observable qualities of the dog (such as appearance, movement, and temperament), separately tested qualities (such as ability or health) are not part of the judging in conformation shows.

As a food source.

Dog meat is consumed in some East Asian countries, including Korea, China, and Vietnam, a practice that dates back to antiquity. It is estimated that 13–16 million dogs are killed and consumed in Asia every year. The BBC claims that, in 1999, more than 6,000 restaurants served soups made from dog meat in South Korea. In Korea, the primary dog breed raised for meat, the nureongi (누렁이), differs from those breeds raised for pets that Koreans may keep in their homes.

The most popular Korean dog dish is gaejang-guk (also called bosintang), a spicy stew meant to balance the body's heat during the summer months; followers of the custom claim this is done to ensure good health by balancing one's gi, or vital energy of the body. A 19th century version of gaejang-guk explains that the dish is prepared by boiling dog meat with scallions and chili powder. Variations of the dish contain chicken and bamboo shoots. While the dishes are still popular in Korea with a segment of the population, dog is not as widely consumed as beef, chicken, and pork.

A CNN report in China dated March 2010 includes an interview with a dog meat vendor who stated that most of the dogs that are available for selling to restaurants are raised in special farms but that there is always a chance that a sold dog is someone's lost pet, although dog pet breeds are not considered edible.

Other cultures, such as Polynesia and pre-Columbian Mexico, also consumed dog meat in their history. However, Western, South Asian, African, and Middle Eastern cultures, in general, regard consumption of dog meat as taboo. In some places, however, such as in rural areas of Poland, dog fat is believed to have medicinal properties—being good for the lungs for instance. Dog meat is also consumed in some parts of Switzerland.

Intelligence and behavior

Intelligence.The domestic dog has a predisposition to exhibit a social intelligence that is uncommon in the animal world. Dogs are capable of learning in a number of ways, such as through simple reinforcement (e.g., classical or operant conditioning) and by observation.

Dogs go through a series of stages of cognitive development. As with humans, the understanding that objects not being actively perceived still remain in existence (called object permanence) is not present at birth. It develops as the young dog learns to interact intentionally with objects around it, at roughly 8 weeks of age.

Puppies learn behaviors quickly by following examples set by experienced dogs. This form of intelligence is not peculiar to those tasks dogs have been bred to perform, but can be generalized to myriad abstract problems. For example, Dachshund puppies that watched an experienced dog pull a cart by tugging on an attached piece of ribbon in order to get a reward from inside the cart learned the task fifteen times faster than those left to solve the problem on their own.

Dogs can also learn by mimicking human behaviors. In one study, puppies were presented with a box, and shown that, when a handler pressed a lever, a ball would roll out of the box. The handler then allowed the puppy to play with the ball, making it an intrinsic reward. The pups were then allowed to interact with the box. Roughly three-quarters of the puppies subsequently touched the lever, and over half successfully released the ball, compared to only 6% in a control group that did not watch the human manipulate the lever. Another study found that handing an object between experimenters who then used the object's name in a sentence successfully taught an observing dog each object's name, allowing the dog to subsequently retrieve the item.

Dogs also demonstrate sophisticated social cognition by associating behavioral cues with abstract meanings. One such class of social cognition involves the understanding that others are conscious agents. Research has shown that dogs are capable of interpreting subtle social cues, and appear to recognize when a human or dog's attention is focused on them. To test this, researchers devised a task in which a reward was hidden underneath one of two buckets. The experimenter then attempted to communicate with the dog to indicate the location of the reward by using a wide range of signals: tapping the bucket, pointing to the bucket, nodding to the bucket, or simply looking at the bucket. The results showed that domestic dogs were better than chimpanzees, wolves, and human infants at this task, and even young puppies with limited exposure to humans performed well.

Psychology research has shown that humans' gaze instinctively moves to the left in order to watch the right side of a person's face, which is related to use of right hemisphere brain for facial recognition, including human facial emotions. Research at the University of Lincoln (2008) shows that dogs share this instinct when meeting a human being, and only when meeting a human being (i.e., not other animals or other dogs). As such they are the only non-primate species known to do so.

Stanley Coren, an expert on dog psychology, states that these results demonstrated the social cognition of dogs can exceed that of even our closest genetic relatives, and that this capacity is a recent genetic acquisition that distinguishes the dog from its ancestor, the wolf. Studies have also investigated whether dogs engaged in partnered play change their behavior depending on the attention-state of their partner. Those studies showed that play signals were only sent when the dog was holding the attention of its partner. If the partner was distracted, the dog instead engaged in attention-getting behavior before sending a play signal.

Coren has also argued that dogs demonstrate a sophisticated theory of mind by engaging in deception, which he supports with a number of anecdotes, including one example wherein a dog hid a stolen treat by sitting on it until the rightful owner of the treat left the room. Although this could have been accidental, Coren suggests that the thief understood that the treat's owner would be unable to find the treat if it were out of view. Together, the empirical data and anecdotal evidence points to dogs possessing at least a limited form of theory of mind.Similar research has been performed by Brian Hare of Duke University, who has shown that dogs outperform both great apes as well as wolves raised by humans in reading human communicative signals.

A study found a third of dogs suffered from anxiety when separated from others.

A border collie named Chaser has learned the names for 1,022 toys after three years of training, so many that her trainers have had to mark the names of the objects lest they forget themselves. This is higher than Rico, another border collie who could remember at least 200 objects.

Behavior.

Although dogs have been the subject of a great deal of behaviorist psychology (e.g. Pavlov's dog), they do not enter the world with a psychological "blank slate". Rather, dog behavior is affected by genetic factors as well as environmental factors. Domestic dogs exhibit a number of behaviors and predispositions that were inherited from wolves.

The Gray Wolf is a social animal that has evolved a sophisticated means of communication and social structure. The domestic dog has inherited some of these predispositions, but many of the salient characteristics in dog behavior have been largely shaped by selective breeding by humans. Thus some of these characteristics, such as the dog's highly developed social cognition, are found only in primitive forms in grey wolves.

The existence and nature of personality traits in dogs have been studied (15329 dogs of 164 different breeds) and five consistent and stable "narrow traits" identified, described as playfulness, curiosity/fearlessness, chase-proneness, sociability and aggressiveness. A further higher order axis for shyness–boldness was also identified.

The average sleep time of a dog is said to be 10.1 hours per day. Like humans, dogs have two main types of sleep: Slow-wave sleep, then Rapid eye movement sleep, the state in which dreams occur.

Dog growl.

A new study in Budapest, Hungary, has found that dogs are able to tell how big another dog is just by listening to its growl. A specific growl is used by dogs to protect their food. The research also shows that dogs do not lie about their size, and this is the first time research has shown animals can determine another's size by the sound it makes. The test, using images of many kinds of dogs, showed a small and big dog and played a growl. The result showed that 20 of the 24 test dogs looked at the image of the appropriate-sized dog first and looked at it longest.

Differences from wolves.

Physical characteristics.

Compared to equally-sized wolves, dogs tend to have 20% smaller skulls, 30% smaller brains, as well as proportionately smaller teeth than other canid species. Dogs require fewer calories to function than wolves. It is thought by certain experts that the dog's limp ears are a result of atrophy of the jaw muscles. The skin of domestic dogs tends to be thicker than that of wolves, with some Inuit tribes favoring the former for use as clothing due to its greater resistance to wear and tear in harsh weather.

Behavioral differences.

Dogs tend to be poorer than wolves at observational learning, being more responsive to instrumental conditioning. Feral dogs show little of the complex social structure or dominance hierarchy present in wolf packs. For example, unlike wolves, the dominant alpha pairs of a feral dog pack do not force the other members to wait for their turn on a meal when scavenging off a dead ungulate as the whole family is free to join in. For dogs, other members of their kind are of no help in locating food items, and are more like competitors.

Feral dogs are primarily scavengers, with studies showing that unlike their wild cousins, they are poor ungulate hunters, having little impact on wildlife populations where they are sympatric. However, feral dogs have been reported to be effective hunters of reptiles in the Galápagos Islands, and free ranging pet dogs are more prone to predatory behavior toward wild animals.

Domestic dogs can be monogamous. Breeding in feral packs can be, but does not have to be restricted to a dominant alpha pair (such things also occur in wolf packs). Male dogs are unusual among canids by the fact that they mostly seem to play no role in raising their puppies, and do not kill the young of other females to increase their own reproductive success. Some sources say that dogs differ from wolves and most other large canid species by the fact that they do not regurgitate food for their young, nor the young of other dogs in the same territory.

However, this difference was not observed in all domestic dogs. Regurgitating of food by the females for the young as well as care for the young by the males has been observed in domestic dogs, dingos as well as in other feral or semi-feral dogs. Regurgitating of food by the females and direct choosing of only one mate has been observed even in those semi-feral dogs of direct domestic dog ancestry. Also regurgitating of food by males has been observed in free-ranging domestic dogs.

0 komentar:

Post a Comment